Half-Pass 2

Half pass on a circle or large pirouette from the perspective of

tensegrity and physical intelligence.

Part II

Instead of increasing the decelerating activity of the inside hind leg, the horse cans also shift the weight on the outside foreleg. The escape is often initiated by the rider using reins effects. The bend of the thoracic spine occurs between the rider's upper thighs and is initiated and adjusted by the rider's upper thighs. The theory of the neck bending the thoracic vertebrae is false. The horse's thoracic spine is between the rider's upper thighs and is influenced by the rider's pelvis and upper thighs. However, while the rider's upper thighs hug the horse's thoracic spine. Efficacy relies on the integrity of the rider's body. When the rider turns, the head, or the shoulders, or the pelvis in the direction of the motion, twisting his or her vertebral column, the twist annihilates the whole dynamics. The horse feels through the rider's upper thighs, the tone of the rider's body. Twisting the spine alters the rider's integrity and efficiency. Tensegrity combines tone and integrity. The tone of the rider's body, including the upper thighs, acts in the direction of the bend.

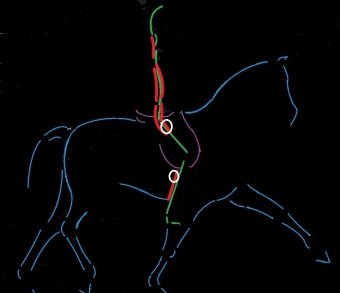

The left picture illustrates the primary muscles used when the rider uses the lower thighs and the knees. The right picture illustrated the muscular system involved in contact with the upper thighs and association of the upper thighs with the pelvis and torso. It is not a gesture; it is a dynamic relation. The rider's inside leg is placed where lateral bending of the thoracic spine occurs in the vicinity of T16. The rider's upper thigh and the calf are approximately on the same vertical line.  The inside leg is acting as a fulcrum, a reference, around which the horse's thoracic spine bends. The concept of the rider being a reference is essential. During the execution of the movement, the horse manages a vast diversity of forces. Some are helping him in keeping the bend and the proper rotation. Other forces, such as gravity, act in the opposite direction and have to be counteracted by the muscular system. This complex interaction of forces is the conversation that the horse and the rider have during the execution of the movement, where the rider guides the horse's mental processing toward the appropriate use of his body.

The inside leg is acting as a fulcrum, a reference, around which the horse's thoracic spine bends. The concept of the rider being a reference is essential. During the execution of the movement, the horse manages a vast diversity of forces. Some are helping him in keeping the bend and the proper rotation. Other forces, such as gravity, act in the opposite direction and have to be counteracted by the muscular system. This complex interaction of forces is the conversation that the horse and the rider have during the execution of the movement, where the rider guides the horse's mental processing toward the appropriate use of his body.

The rider outside leg is a little further back but not much. The reason for a different position of the outside leg merely is avoiding confusion between the action of both legs. There is no need and no advantage in placing the outside leg far back as the muscles touched by the rider leg don't engage the hind leg. The placement of the rider outside leg cannot be done bending the knee as both the upper thigh and the calf are part of the conversation. The placement of the outside leg comes from the hip.

The rider's upper thigh, the pelvis, the vertebral column, the shoulders, and the head are slightly oriented in the direction of the bend. The rider's weight is equal on both seat bones. The brain is set on the idea that while the croup will move slightly laterally, the focus is on the bending of the thoracic spine forward and around the rider's inside leg. The hands ensure that the bending of the cervical vertebrae continues and does not exceed the bending of the thoracic vertebrae.

As the half pass on the circle or large pirouette goes on, the rider might feel some pressure on the outside upper thighs or the calf of the inside leg. Often inverted rotation shifts the horse shoulders toward the outside and the haunches toward the inside. The horse can also shift the whole body toward the outside, and the rider will feel some pressure on the outside upper thigh and calf. This is the conversation that the horse and the rider have during the execution of half pass or any movement. It is not the movement that educates the horse's body. It is the rider's understanding of the conditions that render the gymnastic effective. The dialogue is about guiding the horse's mental processing toward the optimum use of the horse's physique. During the conversation, the rider is the reference. When the horse presses on the rider's upper thigh or calf, the rider adjusts the tone of the whole body with nuances aiming at guiding the horse's mental exploration instead of criticizing the error. The concept of obedience does not permit such conversation as the horse's difficulties are judged as disobedience instead of part of a conversation where the horse describes his actual body state and consequent challenges.

Another standard error during the execution of the large pirouette or half-pass on the circle is the horse shifting the shoulder toward the inside of the circle. This can be due to the difficulty of the horse to bend the thoracic spine forward and around the rider's inside leg. The rider's adjustments have to be decided to have this biomechanics factor in mind. A common error causing this error is pushing the horse shoulders with the outside rein. The hand action often places the poll toward the outside. If the rider does not clearly bend the thoracic spine with the integrity of his or her body, changing to the poll position often changes the bend of the thoracic area. Bending the thoracic spine the wrong way pushes the shoulders toward the inside of the move.

The bending of the thoracic spine in the direction of the motion and above all, the transversal rotation associated with such bending, is, at the level of the thoracic area and forelegs, the main gymnastic and therapeutic effect of the half pass on the circle. The forelegs extrinsic muscles and muscles of the thoracic area have to work intensively in order to maintain lateral bending and proper rotation against gravity, limb action, and combinations of forces acting the opposite way.

When I worked on the video showing the main forces acting in favor or against the proper rotation during half pass, the thought crossed my mind that the horse was too busy to be bothered by the rider's aids. The horse needs the rider's brain. Having in mind the coordination that the horse needs to achieve to benefit from the move, the rider analyses the horse's exploration and guides the horse's research toward efficiency.

Jean Luc Cornille